News

Invasive Stream and Wetland Plants

Invasive non-native plants are a hot topic. Their proliferation causes serious impacts to our local flora, fauna and waterways.

Pennsylvania flora includes 3,091 species of vascular plants – also known as tube plants because they can efficiently move nutrients through their systems.

Of these, 69% evolved in eastern North America. The remaining 31% evolved elsewhere and were brought here through the actions of humans.

Some cultivated plants were brought here deliberately by early European settlers. Others arrived accidentally, by hitching a ride in the ballast water of ships, airplane cargo holds, packing materials, or people’s belongings.

Approximately 95% of introduced plants are well behaved and remain in cultivated fields or gardens, others have spread unchecked.

Invasive Plant Proliferation

Problems caused by non-native plants have been exacerbated by deer over-abundance. White-tailed deer evolved in eastern North America along with native flora, which they recognize as suitable food.

These large herbivores do not eat most non-native plants as long as native vegetation is available. Therefore, heavily browsed areas result in non-native species flourishing at the expense of the native species.

A domino effect continues through the entire ecosystem impacting native flora and fauna alike.

The same scenario occurs in waterways and wetlands. Native aquatic plants, fish and invertebrates, are replaced by non-native species that impact our wetlands and waterways.

The following are a few of these non-native plants found in Pike County, which are changing our aquatic ecosystems.

Japanese Knotweed (Fallopia japonica) & Giant Knotweed (Fallopia sachalinensis)

Both species of knotweed were introduced into North America for ornamental use and forage and erosion control in the late 1800s. Originally from Japan, both species are now found throughout the United States.

These plants can be found in a variety of locations with varying amounts of sun, moisture (banks of waterways, wetlands), and human disturbance. They are herbaceous perennials with hollow, erect stems that are light green, smooth, jointed and swollen at the nodes, hence they are often likened to bamboo.

Japanese knotweed

Japanese Knotweed leaves are squared off at the base whereas Giant knotweeds leaves are heart-shaped. They are known to hybridize, so identification can be challenging.

New shoots can grow three to four inches per day, maturing to three feet to 12 feet tall. Both species have greenish-white flowers and produce a shiny brown seed enclosed in a papery covering.

Seed viability is low. Knotweeds spread primarily by their fleshy roots which are known as rhizomes. These rhizomes can be dispersed by flooding and erosion as well as man-made soil disturbances.

A small piece of rhizome or seed can be carried on machinery, tools or shoes and can root in soil or water where dropped. Knotweeds can form dense colonies that will crowd out native vegetation, clog small waterways, and increase bank erosion lowering the quality of riparian habitat for fish and wildlife. Once established, these stands are very difficult to eradicate.

Purple Loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria)

Purple loosestrife, pictured at the top of this post, was introduced into North American in the early 1800s as an ornamental plant. It was also deposited with the discarded ship ballast. Native to Eurasia, purple loosestrife can now be found throughout much of the United Sates.

Its common name of loosestrife should not be confused with others of the same common name; they are different species. It’s pretty, long-blooming flowers have made it a garden favorite for many years.

Square, woody stems can reach from four feet to 10 feet depending on conditions. It is a perennial with lance shaped leaves arranged in an opposite or whorled pattern on square, woody stems. Magenta-colored flower spikes begin blooming in late June and continue for about six weeks.

Each plant is capable of producing two- to three-million seeds per year with a germination rate of approximately 98%. Seed can be dispersed via wildlife and on machinery, tools, watercraft, shoes and clothing. The plant can also reproduce via underground stems at a rate of one foot per year.

Purple loosestrife prefers open wetlands, and is capable of invading stream banks, pond and lake edges, and ditches. It is a hardy plant that can tolerate a wide range of pH values as well as average soil conditions.

Purple loosestrife outcompetes native plants forming dense, monocultures reducing habitat for waterfowl, clogging waterways, and disrupting nutrient cycling — impacting the entire wetland ecosystem.

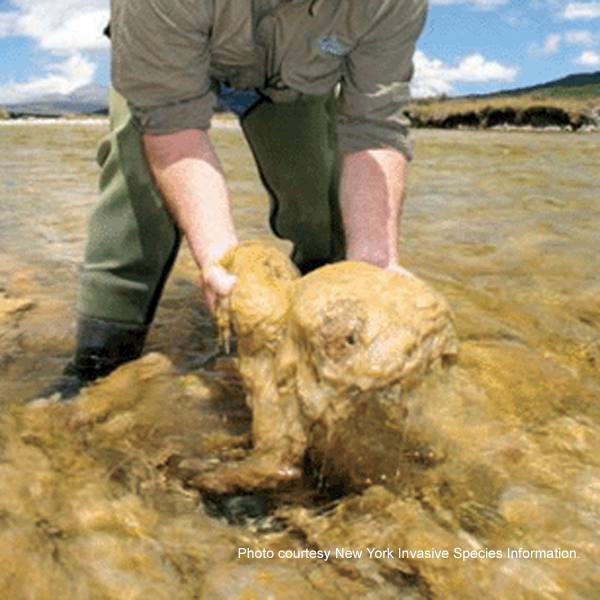

Didymo (Didymosphenia geminate)

Didymo, given the unpleasant common name of rock snot, appeared in Canada in the 1800s but was not a problem until the early 1990s.

Originally from Europe, it was first found in the western US in 2004 and east of the Mississippi in 2005. Since 2007, it has been confirmed in the east and west branches of the Delaware River in NY and PA as well as the main stem of the Delaware River to Callicoon, NY.

Didymo

Didymo is a microscopic algae known as a diatom. In flowing water, didymo may look like toilet tissue. Unlike other algae, didymo feels like wet cotton and isn’t slimy. It varies in color from brown to yellow.

Until recently, the species preferred cold water streams, however, it has been showing up in warmer nutrient-rich streams and rivers. Nuisance blooms are most likely to occurr in flowing rather than stagnant water.

Didymo can be spread by anything that comes into contact with it, including fishing tackle, waders and boats. It is recommended to thoroughly clean and disinfect all equipment before moving to a new body of water, as the individual diatoms are too small to see.

Didymo can cover stream beds with mats as thick as eight inches deep, harming aquatic habitat for native animals as well as plants.

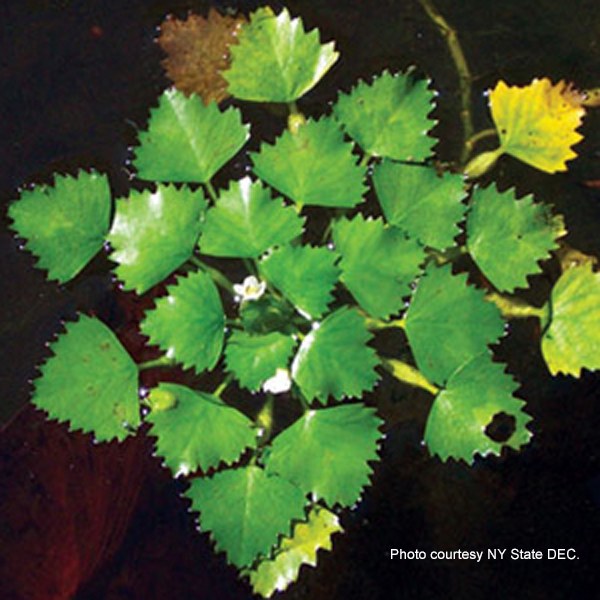

European Water Chestnut (Trapa natans L.)

A native of Eurasia, water chestnut was brought to the U.S. by gardeners in the 1800s, and became quickly established. This annual aquatic plant has submerged leaves and a buoyant rosette of floating glossy, roundly-triangular leaves with toothed edges held on a stem that may reach 15 feet in length. Small, white flowers appear in mid to late July. The hard nut-like seeds with four, short, sharp spines ripen one month later. The seeds are sharp enough to puncture shoe leather.

European water chestnut

The plant can grow in any freshwater body, although it prefers nutrient-rich waters less than 16 feet deep. Water chestnut has a high reproductive rate producing on average 20 seeds per rosette.

The spiny seeds can hitchhike on gear and animals. Most seeds germinate within two years, although remain viable up to 12 years. The plant may also spread vegetatively by any leaf fragment which can re-root elsewhere.

Water chestnut can form dense floating mats that limit oxygen and light for other species. It will outcompete native species for nutrients and space while offering little nutritional value for wildlife. Water chestnut can also damage boats and make swimming dangerous. It can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars to control.

Different methods of control can be used for any of these species with varying degrees of success. It is always best to be aware of what the different species look like and avoid spreading their reach via equipment, tools, shoes or clothing.