News

Down the Drain: Where Does the Water Go?

By PCCD Watershed Specialist Rachael Marques

Ever wonder where the water from your faucet goes? According to Penn State Extension, “about 26% of Pennsylvania households use septic systems.” Septic systems, also called on-lot sewage treatment, are very common in the northeast region of Pennsylvania. They are sometimes almost completely underground with only a pipe or two coming to the surface for inspection and venting. Though these are out of sight, they are a very critical resource for rural homeowners. However, they can also be potential sources of pollution if not maintained properly. Last month’s article noted some of the ways we can conserve our groundwater by mitigating sources of non-point source pollution on the surface; understanding your septic system and taking care of it is another step you can take to help mitigate sources of pollution from reaching our groundwater resources.

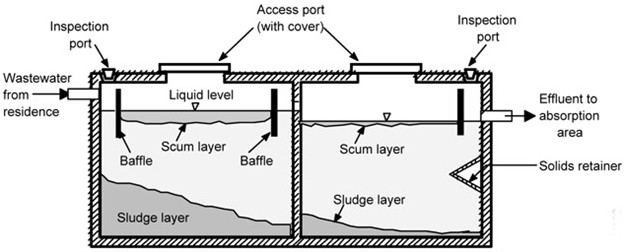

Septic tank diagram, image from Penn State Extension

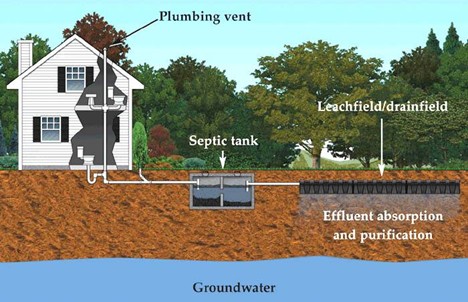

Like our homes, septic systems can come in a variety of shapes and sizes depending on several factors, such as household size. The septic system contains multiple components, but the two major ones are the septic tank (or tanks) and the leach field (or drain field). The tank is where all wastewater from the household goes for initial treatment. You can see in the diagram (right) that once the water goes into the tank, the septic system starts working. Solids will settle to the bottom of the tank, scum such as oils and fats floats to the top, and in the middle, we have our partially treated wastewater. This partially treated water is cleaner than when it went in the tank but not yet ready to meet the water table. This water then flows on to the leach field where the water is slowly released and seeps back into the ground. As the water seeps through the soil back into the groundwater as shown in the diagram (below), organic material left in the water is further decomposed and processed.

Septic system diagram, image from JR’s Inspection Services

Two critical components of this system and how it functions are geology and bacteria! Geology plays an important role in the functionality of our septic systems because, as mentioned in our March article, different soils and geologies have different rates of percolation or rates of allowing water to filter through. Before the system is installed, it goes through a design process. This includes something called a percolation or “perc” test. This test consists of digging several pits and assessing how long water takes to seep into the ground and if the area can host a septic system. This can vary widely depending on the underlaying geology of an area which is why it is a critical first step in design. Oftentimes, there are different designs that can be used, such as installing a sand mound, which can help create a permeable area for the leach field. There are state regulations around the rate of percolation and how many inches of different soil types are required for a typical septic system to function properly. A Sewage Enforcement Officer (SEO) can help you figure out which kind of system will work best for your geology and location. Each municipality has a SEO on staff so contact your local municipal office if you would like more information.

Like geology, bacteria play a critical role in the treatment process within the septic tank(s). They help break down organic material and the solids within the tank which create the sludge at the bottom. If the sludge builds up too much, it can prevent the system from functioning the way it should. This could lead to water being released that is not treated properly, which is one of the most common sources of groundwater contamination! One way to avoid this is having a professional come to pump out the sludge on a regular basis, generally every 3-5 years. This can depend on the size of your tank and the number of people in your household. If you aren’t sure how big your septic system is, a professional can help assess the size and functionality of your system. It is a good idea to also have your system inspected from time to time to assess the tank and other parts for wear and tear.

It is also important to be aware of what you put into your septic system. Household products, especially cleaners, can affect the microbiome (community of bacteria) in your septic system, thus leading to it not treating the water like it is designed to. This can again potentially cause contamination of our groundwater and stream systems. Much like our own microbiomes, when things get out of balance, there can be negative effects! When the bacteria in the septic system are not breaking down the organic waste like they should be, it can be like skipping a step of the treatment process. This can cause unpleasant smells, clogs in the drain field, and even potentially backups into your home! To avoid this, try not to put a lot of bleach, antibacterial products or hazardous wastes down your drains as these can kill the important bacteria in your septic tank! If possible, keep an eye out for “septic-friendly” cleaners and products that will break down in the system without harming the bacteria within. Septic systems are also not designed to treat products like paints, medications, etc., so it is important to dispose of your household hazardous waste properly instead of putting it down the drain.

The last few months’ articles have explored the hydrogeomorphology of our underground resources, but what about what we see on the surface? The rocks and soil under the ground do greatly affect what’s happening above ground, too. Stay tuned for next month’s article to learn more about how geology affects our surface waters, like lakes and rivers.

Additional Resources:

Information from PA DEP on SEOs, septic installation, and system maintenance